I started to learn Chinese a year ago because I felt like learning a new language. I expected it to be challenging, but I also expected to advance faster than I ended up doing. I am still not able to make myself understood not even in the most simple situations. I can recognize some 400 characters, but most of the times, I don’t get the context. For me, learning Chinese is hard. I’d like to share my thoughts on why this is so and how I am trying to cope with it.

I started to learn Chinese a year ago because I felt like learning a new language. I expected it to be challenging, but I also expected to advance faster than I ended up doing. I am still not able to make myself understood not even in the most simple situations. I can recognize some 400 characters, but most of the times, I don’t get the context. For me, learning Chinese is hard. I’d like to share my thoughts on why this is so and how I am trying to cope with it.

The writing system

For a European, learning Chinese is a challenge quite different to learning another European language. In particular, its logosyllabic writing system adds another dimension to the learning process as there is no relation between the pronunciation and the written form of a word. For any language based on an alphabet, a word can be seen as two dimensional: (1) its semantics and (2) its pronunciation and written form, which are directly related. Chinese adds a third dimension by splitting the second, the pronunciation and writing. This additional dimension makes my brain work significantly slower when it comes to remembering a new word.

Now, when learning a European language as a European, say, Spanish as an Austrian, the usual approach is to first know the alphabet and then start off with some useful, every-day language, like the words with the semantics of “please” or “thanks” along with their written form based on the alphabet. For Spanish that would be “por favor” or “gracias”. Try this with Chinese: 謝謝 (or 谢谢 in the simplified version). Pronunciation? Can be tranliterated by “xièxie”. How is this actually pronounced? Well, that again is a different story to which I will get back later.

It is important to know how to say “thank you” and I think that it should be the first phrase one should be able to say in any language. However, a brain completely inexperienced with Chinese characters might not be able to cope with the 3-dimensional attack of semantics, pronunciation, and character. At least mine wasn’t. I ended up spending hours writing the same complex character over and over again with the result of forgetting it three days later. Sounds frustrating and so it was indeed.

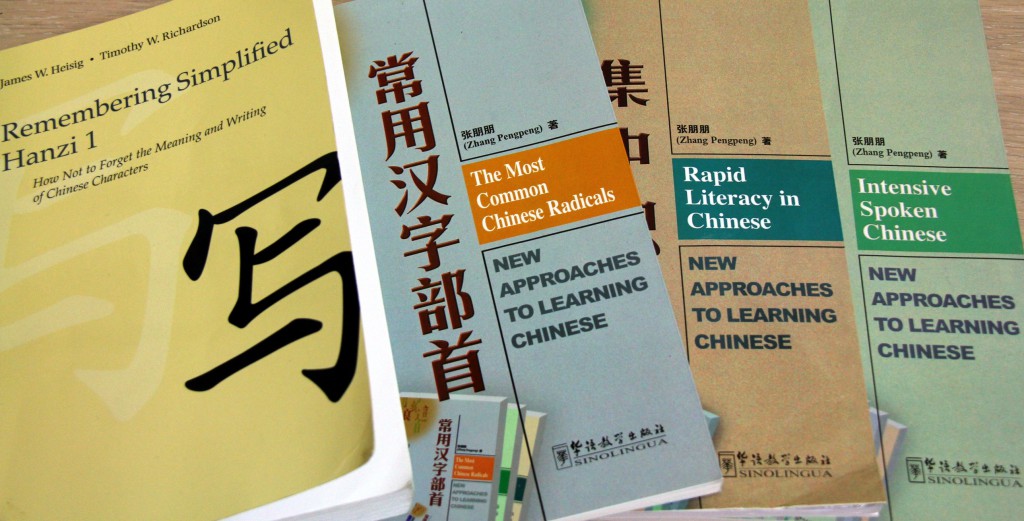

The problem is that the words usually learned first are not the ones represented by the most simple characters. I researched a bit on how other people deal with this problem and found that this had been recognized at least by James W. Heisig, who wrote several books on how to remember Hanzi and Kanji (the Chinese and the Japanese version of the characters), e.g., Remembering Simplified Hanzi, and by Zhang Peng Peng, who wrote the trilogy of “Intensive Spoken Chinese”, “The Most Common Chinese Radicals”, and “Rapid Literacy in Chinese”. Both authors promote a separation of semantics/pronunciation from semantics/character for the reason described above. This means that in the beginning, the student should follow two separate lines of vocabulary: (A) containing words studied with their semantics and their pronunciation, and (B) containing words studied with their semantics and their character. (A) will start with words frequently used in daily language, like “thank you”, or “my name is Alice”. (B) will start with words represented by simple characters, such as 口 (mouth), 日 (sun), 月 (moon) and then follow up with characters containing these characters, like 明 (bright), 朋 (friend), or 唱 (sing). With progress, the overlap of the two sets will increase.

I am currently studying Heisig’s book by myself for the (A) set, and taking Chinese classes (group and individual) and working with Zhang Peng Peng’s “Intensive Spoken Chinese”, which comes with a CD, for the (B) set. For the overlap of the two sets, I use “Rapid Literacy in Chinese”. For both sets, I use hand-made paper flashcards and electronic Anki flashcards. All material concerning (B) is based on the simplified version of the Chinese characters, which for me, being in Taiwan, is not optimal, and I am not yet sure how to deal with it.

The pronunciation

The pronunciation is the second big challenge for a European learning Chinese. It is based on four tones plus a neutral pronunciation. A tone is a certain way of modifying the pitch of a syllable. It can be high and stable (tone 1), rising (tone 2), low and falling, then rising a little bit (tone 3), and falling (tone 4). But it’s not just the tones. Additionally there are many diphtongs and triphtongs and, for many Europeans quite unintuitive, different sounds of “Sh” and “S”.

Several phonetic alphabets have been introduced in the past to transcribe Chinese. The most widely used is Hanyu Pinyin, which is based on the English alphabet with some extensions. In Mainland China, almost all transcriptions are in Hanyu Pinyin. However, here in Taiwan, Pinyin is hardly used anywhere. An alternative system to Pinyin here is Zhuyin fuhao, also known as BoPoMoFo, which is the pronunciation of the first four letters ㄅㄆㄇㄈ. As can be seen, it is not based on the English alphabet. BoPoMoFo consists of 37 letters divided into three groups: (A) Letters that are only used at the beginning of a syllable, (B) letters that are used in the middle or the end, and (C) letters that are only used at the end. Each syllable therefore contains one, two, or three letters in BoPoMoFo. In Taiwan, many books for children have a BoPoMoFo annotation. Since they are usually written in traditional style, that is, top down, this annotation fits in very nicely. I have been learning Pinyin-based Chinese so far, but am currently switching to BoPoMoFo in order to be able to practice with such books. I have the feeling that BoPoMoFo captures the sounds more nicely and helps me to learn them without the bias of the English alphabet towards specific (English, German, or even Spanish) pronunciation.

The grammar

At last, some good news. Most of the complicated grammar we have to deal with in European languages doesn’t exist in Chinese. No articles, no cases, no tenses, no subjunctive, no declination. Only a somewhat strict word order, however, this is actually very useful as it gives good indications when it comes to understanding spoken or written Chinese.